Switching sides on belief in a personal God.

By Richard N. Ostling for the Concord Monitor and New Hampshire Patriot

August 10. 2004

Where God is concerned, two blue-blood theology professors floated in opposite directions and passed each other in midair.

The one thinker is Harvard Divinity School's Gordon D. Kaufman, who was raised in the devoutly evangelical Mennonite faith. His father served as president of the Mennonites' oldest U.S. school, Bethel College in Kansas. Following theological study and clergy ordination, Kaufman gradually adopted radical agnosticism and has long since rejected the supernatural, all-powerful and personal God of the Bible.

Oxford University's Alister McGrath went in the opposite direction. As a youth in Northern Ireland, he enthusiastically embraced atheism and Marxism, figuring that believers were "very stupid people." But advanced study in biochemistry and mature reflection caused McGrath to reconsider. Today he's not just a believer but a leading figure in the conservative wing of the Church of England and world Anglicanism.

Kaufman's latest book, "In the Beginning ... Creativity," denies God as a capital-C Creator. He thinks a lowercase and impersonal "creativity," defined as "the coming into being" of all that's new in the cosmos, is "the only proper object of worship, devotion and faith." To Kaufman, religious concepts are mere "creations of the human imagination," though some might retain the noun "God" to symbolize the mysterious creativity. Notably, his manifesto against the biblical God wasn't issued by a secular publisher but by Fortress Press of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, a slowly declining mainline Protestant denomination.

McGrath has a new book out, too, and it's something else, a bold broadside aptly summarized in the title: "The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World" (Doubleday). Sounds like wishful thinking, considering the widespread disbelief in Britain and continental Europe and in influential U.S. academic and media circles. McGrath doesn't so much prove the near-demise of atheism as claim that, in principle, the props that made it credible and attractive have been rudely knocked aside. His basic theme is that in past centuries, Western faith squandered its moral stature when Christians ran around killing each other and oppressing dissenters. Back then, atheism seemed to promise human liberation.

Today, of course, churches abhor any hint of coerced faith and have long since embraced full freedom of conscience. Meanwhile, when atheistic Communists or neo-pagan Nazis gained political power in the 20th century, McGrath comments, they proved to be even more bloodthirsty than their misguided Christian predecessors and produced "just as many frauds, psychopaths and careerists." The reasonable conclusion: "It is not of the essence of atheism to be a liberator, nor of religion to be an oppressor."

He brackets the "golden age" of atheism between 1789, the start of France's bitterly anti-clerical revolution, and 1989, when the fall of the Berlin Wall announced the death of atheism as a European political force. Though Kaufman decided that science had dethroned the God of old, McGrath concluded from studying the history and philosophy of science that things aren't that simple. He realized that the great atheists (Marx, Freud) presupposed atheism rather than proving it. Thus, "the belief that there is no God is just as much a matter of faith as the belief that there is a God." Impasse. "The grand idea that atheism is the only option for a thinking person has long since passed away." Moreover, McGrath argues, atheism failed in matters of "imagination" and created mere "organizations" instead of the sort of "community" that humans crave, and that religion fosters. Apart from Western Europe, faith is booming.

Still, McGrath maintains a certain respect for his youthful credo. Atheism's past successes showed that "when religion is seen as a threat to the people, it will fail; when it is seen as their friend, it will flourish. Atheism stands in permanent judgment over against arrogant, complacent and superficial Christian churches and leaders."

Welcome to the thoughts that wash up on the sandy beaches on my mind. Paddling is encouraged.. but watch out for the sharks.

About Me

- CyberKitten

- I have a burning need to know stuff and I love asking awkward questions.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

"Nukes Breed Nukes," ElBaradei Warns

From Reuters

May 26, 2006

The United States and other major powers who insist on retaining atomic arsenals set an example that encourages others to follow suit and the world may soon confront a vast expansion in nuclear-armed nations, the head of the U.N. nuclear watchdog said on Thursday.

Mohammed ElBaradei, delivering the commencement address at a prestigious foreign policy school, said it is becoming harder to control the spread of nuclear weapons, despite the international community's best efforts. The speech by the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize winner is likely to have particular resonance at a time when the United States and other major powers are working to persuade Iran to abandon nuclear activities the West says are aimed at building weapons and Tehran says are only for producing energy.

"Nukes breed nukes. As long as some nations continue to insist that nuclear weapons are essential to their security, other nations will want them. There is no way around this simple truth," ElBaradei told the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University." When it comes to nuclear weapons, we are reaching a fork in the road. Either we must begin moving away from a security system based on nuclear weapons or we should resign ourselves to President (John F.) Kennedy's 1960s prediction of a world with 20 to 30 nuclear weapons states," he said. ElBaradei, who heads the International Atomic Energy Agency, said that as recently as a few decades ago, controls on nuclear technology and nuclear material was a sensible strategy for preventing nuclear proliferation.

But "security is no longer as simple as building a wall" and controls aimed at blocking nuclear technology transfers are "no longer enough" in a world in which advanced communications have made it easy to share knowledge, he said. Eventually, efforts to control the spread of such weapons "will only be delaying the inevitable," he predicted. ElBaradei challenged the graduates to help develop an "alternative system of collective security ... that eliminates the need for nuclear deterrence. Only when nuclear weapons states move away from depending on these weapons for their security will the threat of nuclear proliferation by other countries be meaningfully reduced," he said.

He said he did not know what that new security system should look like but suggested that, if the world intensified its efforts to raise living standards in undeveloped countries, "the likelihood of conflict will immediately begin to drop."

From Reuters

May 26, 2006

The United States and other major powers who insist on retaining atomic arsenals set an example that encourages others to follow suit and the world may soon confront a vast expansion in nuclear-armed nations, the head of the U.N. nuclear watchdog said on Thursday.

Mohammed ElBaradei, delivering the commencement address at a prestigious foreign policy school, said it is becoming harder to control the spread of nuclear weapons, despite the international community's best efforts. The speech by the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize winner is likely to have particular resonance at a time when the United States and other major powers are working to persuade Iran to abandon nuclear activities the West says are aimed at building weapons and Tehran says are only for producing energy.

"Nukes breed nukes. As long as some nations continue to insist that nuclear weapons are essential to their security, other nations will want them. There is no way around this simple truth," ElBaradei told the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University." When it comes to nuclear weapons, we are reaching a fork in the road. Either we must begin moving away from a security system based on nuclear weapons or we should resign ourselves to President (John F.) Kennedy's 1960s prediction of a world with 20 to 30 nuclear weapons states," he said. ElBaradei, who heads the International Atomic Energy Agency, said that as recently as a few decades ago, controls on nuclear technology and nuclear material was a sensible strategy for preventing nuclear proliferation.

But "security is no longer as simple as building a wall" and controls aimed at blocking nuclear technology transfers are "no longer enough" in a world in which advanced communications have made it easy to share knowledge, he said. Eventually, efforts to control the spread of such weapons "will only be delaying the inevitable," he predicted. ElBaradei challenged the graduates to help develop an "alternative system of collective security ... that eliminates the need for nuclear deterrence. Only when nuclear weapons states move away from depending on these weapons for their security will the threat of nuclear proliferation by other countries be meaningfully reduced," he said.

He said he did not know what that new security system should look like but suggested that, if the world intensified its efforts to raise living standards in undeveloped countries, "the likelihood of conflict will immediately begin to drop."

Monday, August 28, 2006

The Best Way to Keep us Safe is to Learn the Truth

by Linda McQuaig for the Toronto Star

June 18, 2006

With all eyes glued on the UN Security Council in February 2003, then U.S. secretary of state Colin Powell laid out Washington's case for invading Iraq — based on top-secret intelligence purporting to show Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. As we now know, Powell would have been just as accurate making the case for the existence of the tooth fairy. The eventual revelation that there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq should serve as a constant reminder of the hazard of simply accepting at face value evidence gathered from the shadowy world of intelligence sources. Such evidence is notoriously unreliable, coming from unidentified sources whose knowledge or motives are unknown, or who may have simply confirmed "information" put to them by interrogators in order to end a particularly excruciating bout of torture.

And yet Canadian immigration law allows our authorities to use such evidence — unchallenged — to detain indefinitely an immigrant or refugee claimant they believe might pose a security threat. The Harper government last week defended the government's right to detain people on immigration "security certificates," arguing before the Supreme Court that such sweeping powers are necessary to protect Canadians against terrorism. Five Muslim men have been held in Canada under these certificates for the past few years. But surely the best means of protecting ourselves, not to mention our democracy and the rights of the accused, lies in learning the truth.

The system of security certificates makes it very difficult to learn the truth. Under the system, the accused are tried in secret courts. Neither they nor their lawyers are permitted to know the evidence against them, making it impossible for them to challenge this evidence, whatever it might be. Criminal lawyer Marlys Edwardh notes that this means the judge must weigh the evidence, without any way of knowing the weaknesses in the government's case. The government may, for instance, argue that an accused was at an Al Qaeda training camp at a particular time. How can the judge challenge this, asks Edwardh: "What can he say: Are you sure?"

Meanwhile, the accused is denied the opportunity to present evidence that may show he was fully employed in Canada at the time and, therefore, couldn't have been at the training camp. It's often asserted that, in these cases, there's a clash between the goal of protecting civil liberties and the goal of ensuring the safety of Canadians. But wrong information about terrorist threats does nothing to ensure our safety. Indeed, wrong information can lead us to confuse real and imagined terrorist threats — with possibly dangerous consequences. Is there any evidence that the American people are safer because they invaded Iraq, out of the false belief that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction? If Canadians join U.S. wars — prodded by fears of terrorist plots that may not even be true — it's hard to see how this makes us safer. It might well do the opposite.

by Linda McQuaig for the Toronto Star

June 18, 2006

With all eyes glued on the UN Security Council in February 2003, then U.S. secretary of state Colin Powell laid out Washington's case for invading Iraq — based on top-secret intelligence purporting to show Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. As we now know, Powell would have been just as accurate making the case for the existence of the tooth fairy. The eventual revelation that there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq should serve as a constant reminder of the hazard of simply accepting at face value evidence gathered from the shadowy world of intelligence sources. Such evidence is notoriously unreliable, coming from unidentified sources whose knowledge or motives are unknown, or who may have simply confirmed "information" put to them by interrogators in order to end a particularly excruciating bout of torture.

And yet Canadian immigration law allows our authorities to use such evidence — unchallenged — to detain indefinitely an immigrant or refugee claimant they believe might pose a security threat. The Harper government last week defended the government's right to detain people on immigration "security certificates," arguing before the Supreme Court that such sweeping powers are necessary to protect Canadians against terrorism. Five Muslim men have been held in Canada under these certificates for the past few years. But surely the best means of protecting ourselves, not to mention our democracy and the rights of the accused, lies in learning the truth.

The system of security certificates makes it very difficult to learn the truth. Under the system, the accused are tried in secret courts. Neither they nor their lawyers are permitted to know the evidence against them, making it impossible for them to challenge this evidence, whatever it might be. Criminal lawyer Marlys Edwardh notes that this means the judge must weigh the evidence, without any way of knowing the weaknesses in the government's case. The government may, for instance, argue that an accused was at an Al Qaeda training camp at a particular time. How can the judge challenge this, asks Edwardh: "What can he say: Are you sure?"

Meanwhile, the accused is denied the opportunity to present evidence that may show he was fully employed in Canada at the time and, therefore, couldn't have been at the training camp. It's often asserted that, in these cases, there's a clash between the goal of protecting civil liberties and the goal of ensuring the safety of Canadians. But wrong information about terrorist threats does nothing to ensure our safety. Indeed, wrong information can lead us to confuse real and imagined terrorist threats — with possibly dangerous consequences. Is there any evidence that the American people are safer because they invaded Iraq, out of the false belief that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction? If Canadians join U.S. wars — prodded by fears of terrorist plots that may not even be true — it's hard to see how this makes us safer. It might well do the opposite.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Church schools told not to discriminate in employment

From Ekklesia - 09/03/06

In a landmark ruling church schools have been told they may not to reserve key posts for teachers from their own denomination. An employment tribunal has found in favour of a maths teacher who was turned down for a post at his school because he was not a Roman Catholic reports the Scotsman. David McNab, who is an atheist, has been a maths teacher at St Paul's RC High School in Pollok, Glasgow, since 1991.

But when he applied for the post of acting principal teacher of pastoral care 18 months ago, he was told by the headteacher that he could not be considered for the post as he is not a Catholic. Mr McNab was yesterday awarded £2,000 after the tribunal found he had been "unlawfully discriminated against ... on the grounds of his religion", in contravention of the European Convention on Human Rights, the Scotsman reports. Mr McNab said that he was "very happy and elated" at the judgment.

The tribunal had heard that the school had a system of "reserved posts", such as headteacher or guidance teacher, which could be filled only by candidates who were approved by the Catholic Church. In its ruling yesterday, the tribunal found that the system was not justifiable in law. Church schools often advertise key posts with the requirement that candidates have a Christian faith. Some go further, and specify that sympathy is required with a particular denomination.

Mr McNab, who is currently off work due to stress, said he was treated "like a second-class citizen" when he was told he could not apply for the job. Yesterday, he said: "I'm very glad that the law has been seen to apply to everybody universally. I hope this case brings the system of reserved posts to an end." Jonathan Cornwell, Mr McNab's solicitor, said: "I'm happy that the tribunal has made the right decision."

The ruling comes at a time when church schools are facing growing pressure from both inside and outside churches to tackle their discriminatory admissions and employment policies. The Archbishop of Canterbury will next week give a keynote address at a major conference on church schools, and address the Church of England’s position on religious education, teaching as a vocation, and school admissions policies.

From Ekklesia - 09/03/06

In a landmark ruling church schools have been told they may not to reserve key posts for teachers from their own denomination. An employment tribunal has found in favour of a maths teacher who was turned down for a post at his school because he was not a Roman Catholic reports the Scotsman. David McNab, who is an atheist, has been a maths teacher at St Paul's RC High School in Pollok, Glasgow, since 1991.

But when he applied for the post of acting principal teacher of pastoral care 18 months ago, he was told by the headteacher that he could not be considered for the post as he is not a Catholic. Mr McNab was yesterday awarded £2,000 after the tribunal found he had been "unlawfully discriminated against ... on the grounds of his religion", in contravention of the European Convention on Human Rights, the Scotsman reports. Mr McNab said that he was "very happy and elated" at the judgment.

The tribunal had heard that the school had a system of "reserved posts", such as headteacher or guidance teacher, which could be filled only by candidates who were approved by the Catholic Church. In its ruling yesterday, the tribunal found that the system was not justifiable in law. Church schools often advertise key posts with the requirement that candidates have a Christian faith. Some go further, and specify that sympathy is required with a particular denomination.

Mr McNab, who is currently off work due to stress, said he was treated "like a second-class citizen" when he was told he could not apply for the job. Yesterday, he said: "I'm very glad that the law has been seen to apply to everybody universally. I hope this case brings the system of reserved posts to an end." Jonathan Cornwell, Mr McNab's solicitor, said: "I'm happy that the tribunal has made the right decision."

The ruling comes at a time when church schools are facing growing pressure from both inside and outside churches to tackle their discriminatory admissions and employment policies. The Archbishop of Canterbury will next week give a keynote address at a major conference on church schools, and address the Church of England’s position on religious education, teaching as a vocation, and school admissions policies.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

My Favourite Movies: Gladiator

My Favourite Movies: Gladiator

I have been a fan of sword and sandal epics since my Father took me to see films such as Ben Hur, Cleopatra & even El Cid. Gladiator was most certainly in that mould and although not Russell Crowe’s biggest fan I liked this movie very much. The opening battle scene was one of the best I’ve seen in ages and the later scenes in the Coliseum where quite frankly outstanding. Initially I did think that the middle of the film, full of politicking, was a bit dull but I have grown to like that too. The central characters are well done but watch the secondary characters, its worth the effort.

Anyway – the story is a fairly basic one, that of revenge. Maximus, a celebrated Roman general is betrayed and apparently killed on the orders of the son of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. After failing to save his family, Maximus is sold as a slave and becomes a fearsome gladiator. As his fame and fighting skills grow he finally ends up in Rome to face the man who destroyed his life.

Thinking about things a bit more deeply – as is my want – it came to me that I tend to like films where an individual or small group fights against seemingly impossible odds but ultimately triumph(s) due to bloody hard work and raw talent…. I wonder what that says about my deep psyche.

If you haven’t seen this film why not rent it for a wet Sunday afternoon. Oh, and get some popcorn in…

Friday, August 25, 2006

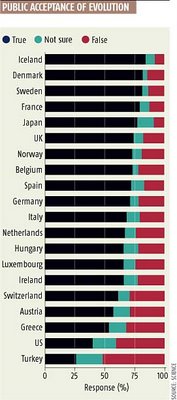

Why Doesn't America Believe in Evolution?

Why Doesn't America Believe in Evolution?

By Jeff Hecht for New Scientist

Sunday 20 August 2006

Human beings, as we know them, developed from earlier species of animals: true or false? This simple question is splitting America apart, with a growing proportion thinking that we did not descend from an ancestral ape. A survey of 32 European countries, the US and Japan has revealed that only Turkey is less willing than the US to accept evolution as fact. Religious fundamentalism, bitter partisan politics and poor science education have all contributed to this denial of evolution in the US, says Jon Miller of Michigan State University in East Lansing, who conducted the survey with his colleagues. "The US is the only country in which [the teaching of evolution] has been politicised," he says. "Republicans have clearly adopted this as one of their wedge issues. In most of the world, this is a non-issue."

Miller's report makes for grim reading for adherents of evolutionary theory. Even though the average American has more years of education than when Miller began his surveys 20 years ago, the percentage of people in the country who accept the idea of evolution has declined from 45 in 1985 to 40 in 2005 (Science, vol 313, p 765). That's despite a series of widely publicised advances in genetics, including genetic sequencing, which shows strong overlap of the human genome with those of chimpanzees and mice. "We don't seem to be going in the right direction," Miller says. There is some cause for hope. Team member Eugenie Scott of the National Center for Science Education in Oakland, California, finds solace in the finding that the percentage of adults overtly rejecting evolution has dropped from 48 to 39 in the same time. Meanwhile the fraction of Americans unsure about evolution has soared, from 7 per cent in 1985 to 21 per cent last year. "That is a group of people that can be reached," says Scott.

The main opposition to evolution comes from fundamentalist Christians, who are much more abundant in the US than in Europe. While Catholics, European Protestants and so-called mainstream US Protestants consider the biblical account of creation as a metaphor, fundamentalists take the Bible literally, leading them to believe that the Earth and humans were created only 6000 years ago. Ironically, the separation of church and state laid down in the US constitution contributes to the tension. In Catholic schools, both evolution and the strict biblical version of human beginnings can be taught. A court ban on teaching creationism in public schools, however, means pupils can only be taught evolution, which angers fundamentalists, and triggers local battles over evolution.

These battles can take place because the US lacks a national curriculum of the sort common in European countries. However, the Bush administration's No Child Left Behind act is instituting standards for science teaching, and the battles of what they should be has now spread to the state level. Miller thinks more genetics should be on the syllabus to reinforce the idea of evolution. American adults may be harder to reach: nearly two-thirds don't agree that more than half of human genes are common to chimpanzees. How would these people respond when told that humans and chimps share 99 per cent of their genes?

Thursday, August 24, 2006

U.S. Losing Terror War because of Iraq, Poll Says

by Bob Deans for the Columbus Dispatch (Ohio)

June 30, 2006

WASHINGTON - The United States is losing its fight against terrorism and the Iraq war is the biggest reason why, more than eight of ten American terrorism and national security experts concluded in a poll released yesterday. One participant in the survey, a former CIA official who described himself as a conservative Republican, said the war in Iraq has provided global terrorist groups with a recruiting bonanza, a valuable training ground and a strategic beachhead at the crossroads of the oil-rich Persian Gulf and Turkey, the traditional land bridge linking the Middle East to Europe. "The war in Iraq broke our back in the war on terror," said the former official, Michael Scheuer, the author of Imperial Hubris, a popular book highly critical of the Bush administration’s anti-terrorism efforts.

"It has made everything more difficult and the threat more existential." Scheuer, a former counterterrorism expert with the CIA, is one of more than 100 national security and terrorism analysts who were surveyed this spring for the nonscientific poll by Foreign Policy magazine and the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning research group headed by John Podesta, who served as White House chief of staff in the Clinton administration. Of the experts queried, 45 identified themselves as liberals, 40 said they were moderates and 31 called themselves conservatives. The pollsters then weighted the responses so that the percentage results reflected one-third participation by each group.

Asked whether the United States is "winning the war on terror," 84 percent said no and 13 percent answered yes. Asked whether the war in Iraq is helping or hurting the global antiterrorism campaign, 87 percent answered that it was undermining those efforts. The public gives Bush higher marks in the anti-terrorism effort than the policy experts. In an ABC News/Washington Post poll taken this past Thursday through Sunday, 57 percent of respondents said America’s efforts to fight terrorism are going well; 41 percent said it is not going well. In the same poll, 59 percent said the country is safer from terrorism today than it was before the Sept. 11 attack, while just 33 percent said the country is less safe. The poll was taken in March and April, before two significant milestones in Iraq: the formation of a new government and the killing by U.S. bombs of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was the top al-Qaida agent in Iraq. It surveyed 1,000 adults nationwide and has a margin of error of 3 percentage points.

The Iraq war was last year’s deadliest, according to Yearbook 2006, the annual evaluation of the world’s conflicts by Sweden’s Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The peace researchers said the number of wars has hit a new low, but that conflict is changing and free-for-all violence in places such as the Congo defies their definitions. "To say conflict as a whole is in decline, I could not draw that conclusion," said Caroline Holmqvist of the institute. The newly released Yearbook 2006 draws from data maintained by Sweden’s Uppsala University. It reports the number of active major armed conflicts worldwide stood at 17 in 2005, the lowest point in a steep slide from a high of 31 in 1991.

by Bob Deans for the Columbus Dispatch (Ohio)

June 30, 2006

WASHINGTON - The United States is losing its fight against terrorism and the Iraq war is the biggest reason why, more than eight of ten American terrorism and national security experts concluded in a poll released yesterday. One participant in the survey, a former CIA official who described himself as a conservative Republican, said the war in Iraq has provided global terrorist groups with a recruiting bonanza, a valuable training ground and a strategic beachhead at the crossroads of the oil-rich Persian Gulf and Turkey, the traditional land bridge linking the Middle East to Europe. "The war in Iraq broke our back in the war on terror," said the former official, Michael Scheuer, the author of Imperial Hubris, a popular book highly critical of the Bush administration’s anti-terrorism efforts.

"It has made everything more difficult and the threat more existential." Scheuer, a former counterterrorism expert with the CIA, is one of more than 100 national security and terrorism analysts who were surveyed this spring for the nonscientific poll by Foreign Policy magazine and the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning research group headed by John Podesta, who served as White House chief of staff in the Clinton administration. Of the experts queried, 45 identified themselves as liberals, 40 said they were moderates and 31 called themselves conservatives. The pollsters then weighted the responses so that the percentage results reflected one-third participation by each group.

Asked whether the United States is "winning the war on terror," 84 percent said no and 13 percent answered yes. Asked whether the war in Iraq is helping or hurting the global antiterrorism campaign, 87 percent answered that it was undermining those efforts. The public gives Bush higher marks in the anti-terrorism effort than the policy experts. In an ABC News/Washington Post poll taken this past Thursday through Sunday, 57 percent of respondents said America’s efforts to fight terrorism are going well; 41 percent said it is not going well. In the same poll, 59 percent said the country is safer from terrorism today than it was before the Sept. 11 attack, while just 33 percent said the country is less safe. The poll was taken in March and April, before two significant milestones in Iraq: the formation of a new government and the killing by U.S. bombs of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was the top al-Qaida agent in Iraq. It surveyed 1,000 adults nationwide and has a margin of error of 3 percentage points.

The Iraq war was last year’s deadliest, according to Yearbook 2006, the annual evaluation of the world’s conflicts by Sweden’s Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The peace researchers said the number of wars has hit a new low, but that conflict is changing and free-for-all violence in places such as the Congo defies their definitions. "To say conflict as a whole is in decline, I could not draw that conclusion," said Caroline Holmqvist of the institute. The newly released Yearbook 2006 draws from data maintained by Sweden’s Uppsala University. It reports the number of active major armed conflicts worldwide stood at 17 in 2005, the lowest point in a steep slide from a high of 31 in 1991.

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Karl Marx, Religion, and Economics

From Austin Cline for About.Com

According to Karl Marx, religion is like other social institutions in that it is dependent upon the material and economic realities in a given society. It has no independent history; instead it is the creature of productive forces. As Marx wrote, “The religious world is but the reflex of the real world.” According to Marx, religion can only be understood in relation to other social systems and the economic structures of society. In fact, religion is only dependent upon economics, nothing else — so much so that the actual religious doctrines are almost irrelevant. This is a functionalist interpretation of religion: understanding religion is dependent upon what social purpose religion itself serves, not the content of its beliefs. Marx’s opinion is that religion is an illusion that provides reasons and excuses to keep society functioning just as it is.

Much as capitalism takes our productive labor and alienates us from its value, religion takes our highest ideals and aspirations and alienates us from them, projecting them onto an alien and unknowable being called a god. Marx has three reasons for disliking religion. First, it is irrational — religion is a delusion and a worship of appearances that avoids recognizing underlying reality. Second, religion negates all that is dignified in a human being by rendering them servile and more amenable to accepting the status quo. In the preface to his doctoral dissertation, Marx adopted as his motto the words of the Greek hero Prometheus who defied the gods to bring fire to humanity: “I hate all gods,” with addition that they “do not recognize man’s self-consciousness as the highest divinity.”

Third, religion is hypocritical. Although it might profess valuable principles, it sides with the oppressors. Jesus advocated helping the poor, but the Christian church merged with the oppressive Roman state, taking part in the enslavement of people for centuries. In the Middle Ages the Catholic Church preached about heaven, but acquired as much property and power as possible. Martin Luther preached the ability of each individual to interpret the Bible, but sided with aristocratic rulers and against peasants who fought against economic and social oppression. According to Marx, this new form of Christianity, Protestantism, was a production of new economic forces as early capitalism developed. New economic realities required a new religious superstructure by which it could be justified and defended.

Marx’s most famous statement about religion comes from a critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law:

Religious distress is at the same time the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of a spiritless situation. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is required for their real happiness. The demand to give up the illusion about its condition is the demand to give up a condition which needs illusions.

This is often misunderstood, perhaps because the full passage is rarely used. In some ways, the quote is presented dishonestly because saying “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature...” leaves out that it is also the “heart of a heartless world.” This is more a critique of society that has become heartless and is even a partial validation of religion that it tries to become its heart. In spite of his obvious dislike of and anger towards religion, Marx did not make religion the primary enemy of workers and communists. Had Marx regarded religion as a more serious enemy, he would have devoted more time to it. Marx is saying that religion is meant to create illusory fantasies for the poor. Economic realities prevent them from finding true happiness in this life, so religion tells them this is OK because they will find true happiness in the next life. Marx is not entirely without sympathy: people are in distress and religion does provide solace, just as people who are physically injured receive relief from opiate-based drugs.

The problem is that opiates fail to fix a physical injury — you only forget your pain and suffering. This can be fine, but only if you are also trying to solve the underlying causes of the pain. Similarly, religion does not fix the underlying causes of people’s pain and suffering — instead, it helps them forget why they are suffering and causes them to look forward to an imaginary future when the pain will cease instead of working to change circumstances now. Even worse, this “drug” is being administered by the oppressors who are responsible for the pain and suffering.

From Austin Cline for About.Com

According to Karl Marx, religion is like other social institutions in that it is dependent upon the material and economic realities in a given society. It has no independent history; instead it is the creature of productive forces. As Marx wrote, “The religious world is but the reflex of the real world.” According to Marx, religion can only be understood in relation to other social systems and the economic structures of society. In fact, religion is only dependent upon economics, nothing else — so much so that the actual religious doctrines are almost irrelevant. This is a functionalist interpretation of religion: understanding religion is dependent upon what social purpose religion itself serves, not the content of its beliefs. Marx’s opinion is that religion is an illusion that provides reasons and excuses to keep society functioning just as it is.

Much as capitalism takes our productive labor and alienates us from its value, religion takes our highest ideals and aspirations and alienates us from them, projecting them onto an alien and unknowable being called a god. Marx has three reasons for disliking religion. First, it is irrational — religion is a delusion and a worship of appearances that avoids recognizing underlying reality. Second, religion negates all that is dignified in a human being by rendering them servile and more amenable to accepting the status quo. In the preface to his doctoral dissertation, Marx adopted as his motto the words of the Greek hero Prometheus who defied the gods to bring fire to humanity: “I hate all gods,” with addition that they “do not recognize man’s self-consciousness as the highest divinity.”

Third, religion is hypocritical. Although it might profess valuable principles, it sides with the oppressors. Jesus advocated helping the poor, but the Christian church merged with the oppressive Roman state, taking part in the enslavement of people for centuries. In the Middle Ages the Catholic Church preached about heaven, but acquired as much property and power as possible. Martin Luther preached the ability of each individual to interpret the Bible, but sided with aristocratic rulers and against peasants who fought against economic and social oppression. According to Marx, this new form of Christianity, Protestantism, was a production of new economic forces as early capitalism developed. New economic realities required a new religious superstructure by which it could be justified and defended.

Marx’s most famous statement about religion comes from a critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law:

Religious distress is at the same time the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of a spiritless situation. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is required for their real happiness. The demand to give up the illusion about its condition is the demand to give up a condition which needs illusions.

This is often misunderstood, perhaps because the full passage is rarely used. In some ways, the quote is presented dishonestly because saying “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature...” leaves out that it is also the “heart of a heartless world.” This is more a critique of society that has become heartless and is even a partial validation of religion that it tries to become its heart. In spite of his obvious dislike of and anger towards religion, Marx did not make religion the primary enemy of workers and communists. Had Marx regarded religion as a more serious enemy, he would have devoted more time to it. Marx is saying that religion is meant to create illusory fantasies for the poor. Economic realities prevent them from finding true happiness in this life, so religion tells them this is OK because they will find true happiness in the next life. Marx is not entirely without sympathy: people are in distress and religion does provide solace, just as people who are physically injured receive relief from opiate-based drugs.

The problem is that opiates fail to fix a physical injury — you only forget your pain and suffering. This can be fine, but only if you are also trying to solve the underlying causes of the pain. Similarly, religion does not fix the underlying causes of people’s pain and suffering — instead, it helps them forget why they are suffering and causes them to look forward to an imaginary future when the pain will cease instead of working to change circumstances now. Even worse, this “drug” is being administered by the oppressors who are responsible for the pain and suffering.

Monday, August 21, 2006

Is US the World's Policeman or an Empire?

by Ted Rall for Common Dreams

Wednesday, August 2, 2006

NEW YORK -- Are we the world's policeman? Or are we an empire? The rest of the world has already made up its mind about us. The president of the Pew Research Center, whose latest poll of foreigners finds they hate the United Stats more than ever, says: "Obviously, when you get many more people saying that the U.S. [is as much of] a threat to world peace as...Iran, it's a measure of how much [the war in Iraq] is sapping good will to the United States." But we Americans remain deeply divided over American values and intentions, and it's high time that we got our story straight.

In 1975 Philip Agee published his explosive memoir of his career as a CIA operative, Inside the Company. The former black ops specialist provided proof for what critics had long suspected, that the United States government had assassinated popularly elected foreign leaders and propped up brutal right-wing dictatorships in countries such as Ecuador, Uruguay, Mexico and Argentina throughout the '60s and '70s. Published in the wake of Watergate and the forced resignation of Richard Nixon, disgust for the dirty dealings described by Agee contributed to a reformist wave that fed Jimmy Carter's successful 1976 bid for the presidency.

Upon taking office Carter declared "the soul of our foreign policy" to be concern for human rights. Carter recalled in a 1997 interview: "I announced that human rights would be a cornerstone or foundation of our entire foreign policy. So I officially designated every U.S. ambassador on earth to be my personal human rights representative, and to have the embassy be a haven for people who suffered from abuse by their own government. And every time a foreign leader met with me, they knew that human rights in their country would be on the agenda. And I think that this was one of the seminal changes that was brought to U.S. policy. And although in the first few weeks of his term my successor Ronald Reagan disavowed this policy and sent an emissary down to Argentina and to Chile and to Brazil--to the military dictators--and said, 'The human rights policy of Carter is over,' it was just a few months before he saw that the American people supported this human rights policy and that it was good for his administration. So after that he became a strong protector of human rights as well."

The media and the public interpreted Carter's human rights-based foreign policy as welcome, radical, and sweeping. There were worrisome inconsistencies: Carter's State Department continued to arm and finance the violent dictators of Haiti, the Philippines and Iran. Nevertheless, the CIA was subjected to budget cuts and Congressional oversight. Subsequent U.S. military involvement in Panama, Somalia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq were wholly or in significant part marketed as attempts to liberate the oppressed and protect human rights. Carter and Reagan convinced Americans of all political stripes that defending the helpless, stopping genocide and overthrowing tyrants were our country's basic duties. We still do. Even though 63 percent of Americans say they approve of their own government's use of torture, 86 percent continue to believe that "promoting and defending human rights in other countries" as a U.S. foreign policy goal is "important." An August 2002 Investor's Business Daily/Christian Science Monitor poll found that 81 percent think that "the impact the U.S. has on the rest of the world [on] democratic values and human rights" is a positive one. If we're so nice, why do they hate us so much? The trouble with putting human rights first is that we have do it all the time, in every case, even when it costs us economically. Integrity requires doing what is right even--especially--when it hurts.

Before Jimmy Carter, American foreign policy was a straightforward and cynical realpolitik. We fought in South Korea and South Vietnam as if we were moving pieces on a Cold War chessboard instead of blasting children to bits; the despotic regimes we defended there were more brutal than their enemies. Afterwards, we became hypocrites. We went into Somalia, which controlled a strategic port of entry for oil tankers, but not Rwanda, which had no significant natural resources. We backed Saddam Hussein when Iraq granted lucrative oil concessions to politically connected multinationals and attacked him when he didn't. A true human rights-based foreign policy would require "regime change" warfare against the biggest evildoers in the world, including those willing to do business with us. What we have now is a Chinese menu pick-one-from-column-A-and-one-from-column-B mishmash. We do whatever we want, then come up with a justification--human rights, WMDs, imminent danger--after the fact.

People liked us better when we didn't pretend to be nice.

by Ted Rall for Common Dreams

Wednesday, August 2, 2006

NEW YORK -- Are we the world's policeman? Or are we an empire? The rest of the world has already made up its mind about us. The president of the Pew Research Center, whose latest poll of foreigners finds they hate the United Stats more than ever, says: "Obviously, when you get many more people saying that the U.S. [is as much of] a threat to world peace as...Iran, it's a measure of how much [the war in Iraq] is sapping good will to the United States." But we Americans remain deeply divided over American values and intentions, and it's high time that we got our story straight.

In 1975 Philip Agee published his explosive memoir of his career as a CIA operative, Inside the Company. The former black ops specialist provided proof for what critics had long suspected, that the United States government had assassinated popularly elected foreign leaders and propped up brutal right-wing dictatorships in countries such as Ecuador, Uruguay, Mexico and Argentina throughout the '60s and '70s. Published in the wake of Watergate and the forced resignation of Richard Nixon, disgust for the dirty dealings described by Agee contributed to a reformist wave that fed Jimmy Carter's successful 1976 bid for the presidency.

Upon taking office Carter declared "the soul of our foreign policy" to be concern for human rights. Carter recalled in a 1997 interview: "I announced that human rights would be a cornerstone or foundation of our entire foreign policy. So I officially designated every U.S. ambassador on earth to be my personal human rights representative, and to have the embassy be a haven for people who suffered from abuse by their own government. And every time a foreign leader met with me, they knew that human rights in their country would be on the agenda. And I think that this was one of the seminal changes that was brought to U.S. policy. And although in the first few weeks of his term my successor Ronald Reagan disavowed this policy and sent an emissary down to Argentina and to Chile and to Brazil--to the military dictators--and said, 'The human rights policy of Carter is over,' it was just a few months before he saw that the American people supported this human rights policy and that it was good for his administration. So after that he became a strong protector of human rights as well."

The media and the public interpreted Carter's human rights-based foreign policy as welcome, radical, and sweeping. There were worrisome inconsistencies: Carter's State Department continued to arm and finance the violent dictators of Haiti, the Philippines and Iran. Nevertheless, the CIA was subjected to budget cuts and Congressional oversight. Subsequent U.S. military involvement in Panama, Somalia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq were wholly or in significant part marketed as attempts to liberate the oppressed and protect human rights. Carter and Reagan convinced Americans of all political stripes that defending the helpless, stopping genocide and overthrowing tyrants were our country's basic duties. We still do. Even though 63 percent of Americans say they approve of their own government's use of torture, 86 percent continue to believe that "promoting and defending human rights in other countries" as a U.S. foreign policy goal is "important." An August 2002 Investor's Business Daily/Christian Science Monitor poll found that 81 percent think that "the impact the U.S. has on the rest of the world [on] democratic values and human rights" is a positive one. If we're so nice, why do they hate us so much? The trouble with putting human rights first is that we have do it all the time, in every case, even when it costs us economically. Integrity requires doing what is right even--especially--when it hurts.

Before Jimmy Carter, American foreign policy was a straightforward and cynical realpolitik. We fought in South Korea and South Vietnam as if we were moving pieces on a Cold War chessboard instead of blasting children to bits; the despotic regimes we defended there were more brutal than their enemies. Afterwards, we became hypocrites. We went into Somalia, which controlled a strategic port of entry for oil tankers, but not Rwanda, which had no significant natural resources. We backed Saddam Hussein when Iraq granted lucrative oil concessions to politically connected multinationals and attacked him when he didn't. A true human rights-based foreign policy would require "regime change" warfare against the biggest evildoers in the world, including those willing to do business with us. What we have now is a Chinese menu pick-one-from-column-A-and-one-from-column-B mishmash. We do whatever we want, then come up with a justification--human rights, WMDs, imminent danger--after the fact.

People liked us better when we didn't pretend to be nice.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

This is the (Post) Modern World……

I’ve been thinking for some time now about what it means to be ‘modern’. What is actually meant by modern, what the heck is post-modern and just when did the modern world start?

Some years ago when I was settling on a University course I was keen to study History (one of my many intellectual passions) but couldn’t decide on whether to study Ancient History or Modern History – both of which interest me for different reasons. One of the things I found rather odd was that no University seemed to agree on just what Ancient and especially Modern History actually meant. One course, I think at Coventry University split Ancient & Modern at the point of the Fall of the Roman Empire and I thought – hold on - ‘Modern’ History began in 476AD? Personally I would have placed it just a bit later than that. Then I got my thinking hat on… just when did I think ‘Modern’ History did start?

So I mused. My first thought was August 1945. Why? Because it heralded the beginning of the Atomic Age with the dropping of the Atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Then I thought that maybe 1945 is just too recent. My next thought was 1912 and the sinking of the Titanic which was a major blow to Victorian confidence later shattered by the First World War – things were certainly never the same after that. Going back a bit further I thought of the American Civil War (1861-64) which was arguably the first fully industrialised war. Of course a huge event in the previous century was the Industrial Revolution (around 1750) which changed the course of the world forever. Could that be the start of the ‘Modern’ age? I think that it’s a pretty good candidate. Finally, going back even further, I thought of the Italian Renaissance. Standing as it does between the Medieval world of the Dark Ages and what certainly started to look like a world we would recognise with International Banking, the beginnings of Capitalism, the Nation State taking precedence over the Church and the first forays into what we consider to be science. I certainly couldn’t bring myself to go back any further than the 15th century though and still call it anything like ‘modern’ times.

What do you think? When did we arrive in the Modern Age and what are your reasons for thinking so?

I’ve been thinking for some time now about what it means to be ‘modern’. What is actually meant by modern, what the heck is post-modern and just when did the modern world start?

Some years ago when I was settling on a University course I was keen to study History (one of my many intellectual passions) but couldn’t decide on whether to study Ancient History or Modern History – both of which interest me for different reasons. One of the things I found rather odd was that no University seemed to agree on just what Ancient and especially Modern History actually meant. One course, I think at Coventry University split Ancient & Modern at the point of the Fall of the Roman Empire and I thought – hold on - ‘Modern’ History began in 476AD? Personally I would have placed it just a bit later than that. Then I got my thinking hat on… just when did I think ‘Modern’ History did start?

So I mused. My first thought was August 1945. Why? Because it heralded the beginning of the Atomic Age with the dropping of the Atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Then I thought that maybe 1945 is just too recent. My next thought was 1912 and the sinking of the Titanic which was a major blow to Victorian confidence later shattered by the First World War – things were certainly never the same after that. Going back a bit further I thought of the American Civil War (1861-64) which was arguably the first fully industrialised war. Of course a huge event in the previous century was the Industrial Revolution (around 1750) which changed the course of the world forever. Could that be the start of the ‘Modern’ age? I think that it’s a pretty good candidate. Finally, going back even further, I thought of the Italian Renaissance. Standing as it does between the Medieval world of the Dark Ages and what certainly started to look like a world we would recognise with International Banking, the beginnings of Capitalism, the Nation State taking precedence over the Church and the first forays into what we consider to be science. I certainly couldn’t bring myself to go back any further than the 15th century though and still call it anything like ‘modern’ times.

What do you think? When did we arrive in the Modern Age and what are your reasons for thinking so?

Gates Breaks Ranks with Attack on US AIDS Policy

by Sarah Boseley for the Guardian

August 15, 2006

Bill and Melinda Gates came off the political fence yesterday and backed key causes of Aids campaigners, criticising the abstinence policies advocated by the US government and calling for more rights for women and help for sex workers.

Making the keynote speech of the opening session of the 16th International Aids conference in Toronto, Canada, the Microsoft billionaire and his wife spoke with passion and commitment about the social changes necessary to stop the spread of HIV/Aids. The so-called ABC programme - abstain, be faithful and use a condom - has saved many lives, Mr Gates told the conference of more than 20,000 delegates. But he said that for many at the highest risk of infection, ABC had its limits. "Abstinence is often not an option for poor women and girls who have no choice but to marry at an early age. Being faithful will not protect a woman whose partner is not faithful. And using condoms is not a decision that a woman can make by herself; it depends on a man.

"We need to put the power to prevent HIV in the hands of women. This is true whether the woman is a faithful married mother of small children or a sex worker trying to scrape out a living in a slum. No matter where she lives or what she does, a woman should never need her partner's permission to save her own life." The Gates Foundation is funding research into microbicides - gels or barrier creams that a woman can use before sex and that could destroy the virus.

Mrs Gates called for an end to the stigma that affects those with HIV. "Stigma makes it easier for political leaders to stand in the way of saving lives," she said, in an attack on some African leaders influenced by the pro-abstinence agenda of the Bush government and the Christian fundamentalist right in the US. "In some countries with widespread Aids epidemics, leaders have declared the distribution of condoms immoral, ineffective or both. Some have argued that condoms do not protect against HIV, but in fact help spread it. This is a serious obstacle to ending Aids ... If you oppose the distribution of condoms, something is more important to you than saving lives," she said.

The promotion of abstinence is a key policy of George Bush's $15bn (£7.9bn) five-year President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (Pepfar). By law, 33% of funding must be spent on policies that promote abstinence outside of marriage.The UN special envoy for HIV/Aids to Africa, Stephen Lewis, accused the Bush government of neo-colonialism. He has given his backing to US Congresswoman Barbara Lee, who has introduced legislation to get the abstinence-first rule overturned. "No government in the western world has the right to dictate policy to African governments around the way in which they structure their response to the pandemic," he said. Ms Lee, one of the chief authors of the Pepfar legislation, said she had the backing of 80 members of Congress and 70 non-governmental Aids organisations.

"For women, the abstinence-until-marriage policies make no sense when they face gender discrimination, violence and rape and can't control their own bodies," she said. Jodi Jacobson, executive director of the Centre for Health and Gender Equity in the US, said that in some African countries abstinence policies were absorbing much more than 33% of Pepfar's prevention funding. "In Nigeria nearly 70% went to abstinence-until-marriage policies. In Tanzania, the newest grant is 95% on abstinence and be faithful programmes for youth aged 15-24," she said.

by Sarah Boseley for the Guardian

August 15, 2006

Bill and Melinda Gates came off the political fence yesterday and backed key causes of Aids campaigners, criticising the abstinence policies advocated by the US government and calling for more rights for women and help for sex workers.

Making the keynote speech of the opening session of the 16th International Aids conference in Toronto, Canada, the Microsoft billionaire and his wife spoke with passion and commitment about the social changes necessary to stop the spread of HIV/Aids. The so-called ABC programme - abstain, be faithful and use a condom - has saved many lives, Mr Gates told the conference of more than 20,000 delegates. But he said that for many at the highest risk of infection, ABC had its limits. "Abstinence is often not an option for poor women and girls who have no choice but to marry at an early age. Being faithful will not protect a woman whose partner is not faithful. And using condoms is not a decision that a woman can make by herself; it depends on a man.

"We need to put the power to prevent HIV in the hands of women. This is true whether the woman is a faithful married mother of small children or a sex worker trying to scrape out a living in a slum. No matter where she lives or what she does, a woman should never need her partner's permission to save her own life." The Gates Foundation is funding research into microbicides - gels or barrier creams that a woman can use before sex and that could destroy the virus.

Mrs Gates called for an end to the stigma that affects those with HIV. "Stigma makes it easier for political leaders to stand in the way of saving lives," she said, in an attack on some African leaders influenced by the pro-abstinence agenda of the Bush government and the Christian fundamentalist right in the US. "In some countries with widespread Aids epidemics, leaders have declared the distribution of condoms immoral, ineffective or both. Some have argued that condoms do not protect against HIV, but in fact help spread it. This is a serious obstacle to ending Aids ... If you oppose the distribution of condoms, something is more important to you than saving lives," she said.

The promotion of abstinence is a key policy of George Bush's $15bn (£7.9bn) five-year President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (Pepfar). By law, 33% of funding must be spent on policies that promote abstinence outside of marriage.The UN special envoy for HIV/Aids to Africa, Stephen Lewis, accused the Bush government of neo-colonialism. He has given his backing to US Congresswoman Barbara Lee, who has introduced legislation to get the abstinence-first rule overturned. "No government in the western world has the right to dictate policy to African governments around the way in which they structure their response to the pandemic," he said. Ms Lee, one of the chief authors of the Pepfar legislation, said she had the backing of 80 members of Congress and 70 non-governmental Aids organisations.

"For women, the abstinence-until-marriage policies make no sense when they face gender discrimination, violence and rape and can't control their own bodies," she said. Jodi Jacobson, executive director of the Centre for Health and Gender Equity in the US, said that in some African countries abstinence policies were absorbing much more than 33% of Pepfar's prevention funding. "In Nigeria nearly 70% went to abstinence-until-marriage policies. In Tanzania, the newest grant is 95% on abstinence and be faithful programmes for youth aged 15-24," she said.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

Science versus religion? No contest

by Ian Tattersall for Natural History Magazine

April, 2002

Why do some (only some) of those with profoundly felt religious beliefs feel threatened by aspects of the very science that has brought them the material comfort and security they appear happy to accept? Presumably it is because they think that in some sense, scientific and religious beliefs are in conflict. Nothing, though, could be further from the truth. Science and religion deal in totally different forms of knowledge. Religions seek ultimate truth and do so in a variety of ways. But no really honest scientist would claim to be doing anything like the same thing. Science is a matter of honing our perceptions of ourselves and of the world around us, of producing an increasingly accurate description of our physical and biological environments and how they work. What science emphatically is not is an absolutist system of belief. Rather, it is constantly subject to rearrangement and change as our collective knowledge increases. How can we make progress in science if what we believe today cannot be shown tomorrow to be somehow wrong or at least incomplete? Religious knowledge is in principle eternal, but scientific knowledge is by its very nature provisional.

Being human, some scientists clearly like to bask in an aura of authoritativeness, and certainly nothing is more intimidating to the average person than the stereotypical image of a white-coated figure covering a blackboard with incomprehensible symbols. But in actual fact, scientists are in pursuit of knowledge about mundane realities and are not in the business of revealing timeless truths. And because science is self-correcting, its practitioners can often find themselves pursuing blind alleys.

Some scientists who dispute Darwinian theory apparently do not understand or accept this distinction between scientific knowledge and religious knowledge. Interestingly, many such people are involved in the physical sciences and engineering, areas in which hypotheses tend to be more directly testable than are hypotheses in biology. Indeed, intelligent design, which is offered as an alternative to evolution by natural selection, is essentially an engineering concept. But just look at nature with an engineer's eyes: undoubtedly it works, but this does not mean that organisms are optimized in the way that an intelligent engineer would strive to ensure. There is no better way to illustrate this than by considering our own much-vaunted species, Homo sapiens. As a result of our upright, bipedal posture, we surfer a huge catalogue of woes, including slipped disks, fallen arches, wrenched knees, hernias, and aching necks. No engineer, given the opportunity to design human beings from the ground up, would ever dream of confecting a jury-rigged body plan such as ours. But our innumerable afflictions can be understood as the consequence of adapting an ancestral four-legged body to a new, bipedal lifestyle.

Rather like the myriad infuriating versions of Windows, we humans have been cobbled together from preexisting components. Of course, there may be upsides to this, too. Thus I would guess that our extraordinary human consciousness results not from any specific structures we have acquired but rather from the complex accretionary history of our brain and its consequent untidy nature. Artificial intelligence--specifically because it is engineered--is unlikely ever to match our own strange but unique brand of smarts.

Given the current social climate and the unease that science often engenders, scientists would do well to insist on educating students better about what the profession actually involves. For if our young people think of science as monolithic and authoritarian, they are likely to have excessively high expectations for it and to be disappointed by the inevitable cases in which scientific hypotheses turn out to be wrong. Evolutionary theory is deficient because it is "just a hypothesis"? If so, then we might as well throw out all of science, for the same is true of all scientific knowledge.

by Ian Tattersall for Natural History Magazine

April, 2002

Why do some (only some) of those with profoundly felt religious beliefs feel threatened by aspects of the very science that has brought them the material comfort and security they appear happy to accept? Presumably it is because they think that in some sense, scientific and religious beliefs are in conflict. Nothing, though, could be further from the truth. Science and religion deal in totally different forms of knowledge. Religions seek ultimate truth and do so in a variety of ways. But no really honest scientist would claim to be doing anything like the same thing. Science is a matter of honing our perceptions of ourselves and of the world around us, of producing an increasingly accurate description of our physical and biological environments and how they work. What science emphatically is not is an absolutist system of belief. Rather, it is constantly subject to rearrangement and change as our collective knowledge increases. How can we make progress in science if what we believe today cannot be shown tomorrow to be somehow wrong or at least incomplete? Religious knowledge is in principle eternal, but scientific knowledge is by its very nature provisional.

Being human, some scientists clearly like to bask in an aura of authoritativeness, and certainly nothing is more intimidating to the average person than the stereotypical image of a white-coated figure covering a blackboard with incomprehensible symbols. But in actual fact, scientists are in pursuit of knowledge about mundane realities and are not in the business of revealing timeless truths. And because science is self-correcting, its practitioners can often find themselves pursuing blind alleys.

Some scientists who dispute Darwinian theory apparently do not understand or accept this distinction between scientific knowledge and religious knowledge. Interestingly, many such people are involved in the physical sciences and engineering, areas in which hypotheses tend to be more directly testable than are hypotheses in biology. Indeed, intelligent design, which is offered as an alternative to evolution by natural selection, is essentially an engineering concept. But just look at nature with an engineer's eyes: undoubtedly it works, but this does not mean that organisms are optimized in the way that an intelligent engineer would strive to ensure. There is no better way to illustrate this than by considering our own much-vaunted species, Homo sapiens. As a result of our upright, bipedal posture, we surfer a huge catalogue of woes, including slipped disks, fallen arches, wrenched knees, hernias, and aching necks. No engineer, given the opportunity to design human beings from the ground up, would ever dream of confecting a jury-rigged body plan such as ours. But our innumerable afflictions can be understood as the consequence of adapting an ancestral four-legged body to a new, bipedal lifestyle.

Rather like the myriad infuriating versions of Windows, we humans have been cobbled together from preexisting components. Of course, there may be upsides to this, too. Thus I would guess that our extraordinary human consciousness results not from any specific structures we have acquired but rather from the complex accretionary history of our brain and its consequent untidy nature. Artificial intelligence--specifically because it is engineered--is unlikely ever to match our own strange but unique brand of smarts.

Given the current social climate and the unease that science often engenders, scientists would do well to insist on educating students better about what the profession actually involves. For if our young people think of science as monolithic and authoritarian, they are likely to have excessively high expectations for it and to be disappointed by the inevitable cases in which scientific hypotheses turn out to be wrong. Evolutionary theory is deficient because it is "just a hypothesis"? If so, then we might as well throw out all of science, for the same is true of all scientific knowledge.

Friday, August 18, 2006

Britons Tire of Cruel, Vulgar US: Poll

by Agence France Presse

July 3, 2006

People in Britain view the United States as a vulgar, crime-ridden society obsessed with money and led by an incompetent president whose Iraq policy is failing, according to a newspaper poll. The United States is no longer a symbol of hope to Britain and the British no longer have confidence in their transatlantic cousins to lead global affairs, according to the poll published in The Daily Telegraph.

The YouGov poll found that 77 percent of respondents disagreed with the statement that the US is "a beacon of hope for the world". As Americans prepared to celebrate the 230th anniversary of their independence on Tuesday, the poll found that only 12 percent of Britons trust them to act wisely on the global stage. This is half the number who had faith in the Vietnam-scarred White House of 1975. A massive 83 percent of those questioned said that the United States doesn't care what the rest of the world thinks. With much of the worst criticism aimed at the US adminstration, the poll showed that 70 percent of Britons like Americans a lot or a little.

US President George W. Bush fared significantly worse, with just one percent rating him a "great leader" against 77 percent who deemed him a "pretty poor" or "terrible" leader. More than two-thirds who offered an opinion said America is essentially an imperial power seeking world domination. And 81 per cent of those who took a view said President George W Bush hypocritically championed democracy as a cover for the pursuit of American self-interests. US policy in Iraq was similarly derided, with only 24 percent saying they felt that the US military action there was helping to bring democracy to the country. A spokesman for the American embassy said that the poll's findings were contradicted by its own surveys.

"We question the judgment of anyone who asserts the world would be a better place with Saddam still terrorizing his own nation and threatening people well beyond Iraq's borders," the paper quoted the unnamed spokesman as saying. "With respect to the poll's assertions about American society, we bear some of the blame for not successfully communicating America's extraordinary dynamism. But frankly, so do you (the British press)."

In answer to other questions, a majority of the Britons questions described Americans as uncaring, divided by class, awash in violent crime, vulgar, preoccupied with money, ignorant of the outside world, racially divided, uncultured and in the most overwhelming result (90 percent of respondents) dominated by big business.

[I actually blame quite a few of these beliefs on the American shows we see on our TV screens. If they're not crimes shows they're horrid 'reality TV shows that are designed to show people in the bad light.]

by Agence France Presse

July 3, 2006

People in Britain view the United States as a vulgar, crime-ridden society obsessed with money and led by an incompetent president whose Iraq policy is failing, according to a newspaper poll. The United States is no longer a symbol of hope to Britain and the British no longer have confidence in their transatlantic cousins to lead global affairs, according to the poll published in The Daily Telegraph.

The YouGov poll found that 77 percent of respondents disagreed with the statement that the US is "a beacon of hope for the world". As Americans prepared to celebrate the 230th anniversary of their independence on Tuesday, the poll found that only 12 percent of Britons trust them to act wisely on the global stage. This is half the number who had faith in the Vietnam-scarred White House of 1975. A massive 83 percent of those questioned said that the United States doesn't care what the rest of the world thinks. With much of the worst criticism aimed at the US adminstration, the poll showed that 70 percent of Britons like Americans a lot or a little.

US President George W. Bush fared significantly worse, with just one percent rating him a "great leader" against 77 percent who deemed him a "pretty poor" or "terrible" leader. More than two-thirds who offered an opinion said America is essentially an imperial power seeking world domination. And 81 per cent of those who took a view said President George W Bush hypocritically championed democracy as a cover for the pursuit of American self-interests. US policy in Iraq was similarly derided, with only 24 percent saying they felt that the US military action there was helping to bring democracy to the country. A spokesman for the American embassy said that the poll's findings were contradicted by its own surveys.

"We question the judgment of anyone who asserts the world would be a better place with Saddam still terrorizing his own nation and threatening people well beyond Iraq's borders," the paper quoted the unnamed spokesman as saying. "With respect to the poll's assertions about American society, we bear some of the blame for not successfully communicating America's extraordinary dynamism. But frankly, so do you (the British press)."

In answer to other questions, a majority of the Britons questions described Americans as uncaring, divided by class, awash in violent crime, vulgar, preoccupied with money, ignorant of the outside world, racially divided, uncultured and in the most overwhelming result (90 percent of respondents) dominated by big business.

[I actually blame quite a few of these beliefs on the American shows we see on our TV screens. If they're not crimes shows they're horrid 'reality TV shows that are designed to show people in the bad light.]

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Equipose: Balancing Skepticism and Objectivity

From Austin Cline for About.Com

Being skeptical means engaging claims critically and with doubts. Being objective means not pre-judging a claim and allowing for the possibility of coming to accept it as true, if good enough reasons are provided. People should be both skeptical and objective, but it's possible for them to come into conflict if one isn't careful. In the January / February 2006 Skeptical Inquirer, David Koepsell writes:

An initial standpoint of objectivity is central to the skeptical approach. In research and medical ethics, we call this standpoint “equipoise” (Macrina 2000).

Equipoise means beginning one’s research, investigation, or diagnosis without bias. Equipoise is essential so that the investigation can be pursued adequately, as bias can influence data acquisition. If an investigator begins acquiring data with an aim toward finding something in particular, then one is apt to discard some data, or misinterpret data, even potentially unconsciously, in order to confirm one’s hypothesis. There are numerous historical examples of how a lack of equipoise can influence data collection, and has done so sometimes disastrously.

Unfortunately, this sort of problem occurs without one even realizing it. Of course people have beliefs they want to be true — it’s rare that people want to be wrong, after all. This is why the scientific method relies so heavily on peer review: we may seek out confirming evidence while ignoring data that counts against our beliefs, but our peers may not. Our peers may see what we don’t see.

Of course, equipoise requires an attitude of non-dogmatism. The only thing we are dogmatic about as skeptics and scientists is the method of the sciences itself. This method necessarily begins with doubt, so that we begin a scientific investigation without a presupposition about its outcome. Skeptics or scientists who set out with the assumption that a particular thing is impossible must be open to having that assumption falsified. A dogmatic belief that a particular phenomenon is impossible is itself unscientific, because falsifiability is one of the cornerstones of scientific hypothesis. Thus, a true scientist and a good investigator begins with an objective standpoint, where he or she may have any original assumptions proven wrong by the data.